The Construction of Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B

A very personal and technical written and photographic history, by James MacLaren.

Page 55: Hammerhead Crane TPS Inspection Spider Basket Trolley Support Extensible Pipe Boom Psychosis.

| Pad B Stories - Table of Contents |

And how in the name of hell am I ever going to be able to properly tell you the tale of this thing?

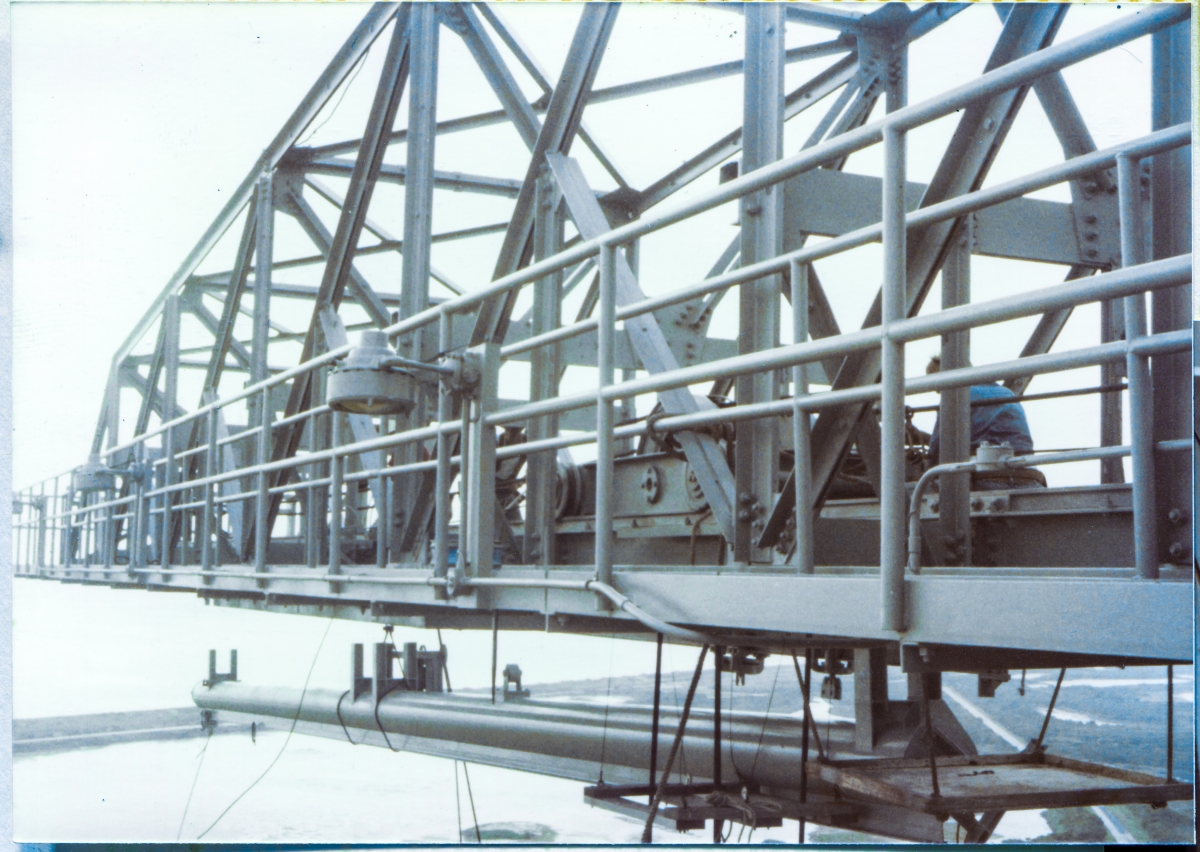

The Extensible Pipe Boom System (it never seemed to have been given an "official" name or acronym, like maybe "Monorail Transfer Doors" or "OMBUU" or anything like that, and I'm going to call it variously whatever the hell I feel like calling it at any given time) carrying a welded-on monorail beam along the full length of its underside, which contraption you see here in suspension, shortly before it was connected to the underside of the Hammerhead Crane Boom, may have been even more stupid and dangerous than the OMS Pod Heated Purge covers, but at least they reconsidered it prior to ever putting a human into it on Pad B, and tore it down and threw it away before anybody was given a chance to get inside of the spider basket which was to dangle beneath it, running a very real risk of injuring or killing themselves, possibly destroying a Space Shuttle in the process.

It's straight out of a Kafka novel. Lifted, verbatim.

And not only was it dangerous as hell in overall concept and intended use, it was dangerous as hell to install, too.

And it was cooked-up somewhere along the line after somebody reconsidered the fact that once the complete Space Shuttle Stack had been rolled out, and was now sitting on its Launch Pad, an awful lot of its surface area was going become inaccessible, and I guess somebody kinda maybe thought better of it, and, not really knowing exactly when or why a thing like this might be needed to kinda maybe get somebody out there to give one of those inaccessible places a look...

...just in case they might need to at some point?

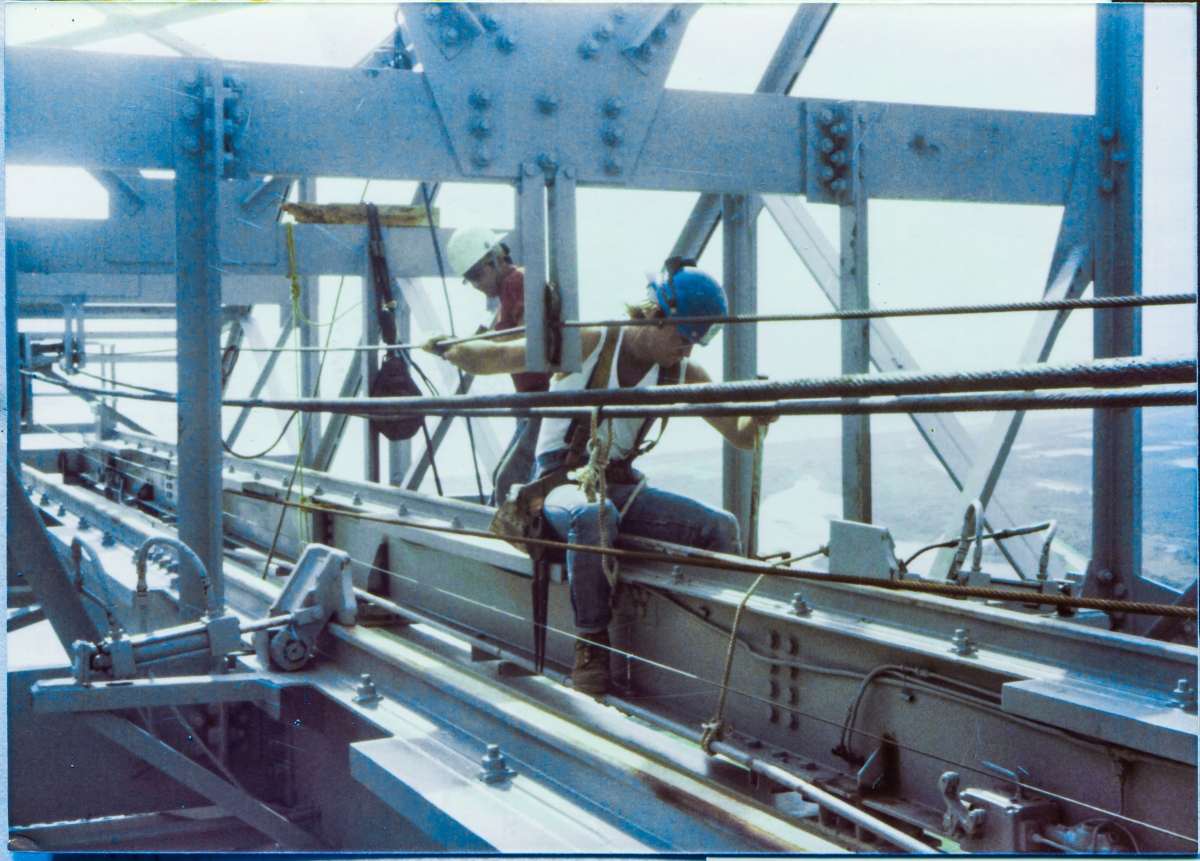

Here's a photograph, taken very shortly after the first image at the top of this page was taken, of James Dixon, up on the Hammerhead Crane Boom, sitting directly on the Crane Hook Trolley Rail, legs straddling the W14x30 main framing member of the Crane Boom, which the Fixed Monorail Psychosis part of the Overall Psychosis got attached to the underside of, a small bit of which can be seen down there below it in this image, as work with the Pipe Boom portion of the Psychosis proceeds out of view beneath him.

And here's a shot of Steve Parker, with an incredulous look on his face, an instant after the roaring west wind that was blowing this day snatched his hardhat off his head, and sent it spinning 300 feet down to the bottom of the Flame Trench.

And now I'm going to have to tell this story, and yes, this set of photo-essays is, among other things, a well-researched and highly-detailed history of things, and for me to tell the tale, we're gonna have to go digging into the history of things to figure out how and why they arrived at such a crack-brained "solution" to one of the problems we've been slowly, ever so slowly, getting drawn farther and farther into, and that problem revolves around the business of leaving a Space Shuttle sitting outside for surprisingly long periods of time, prior to launching it, without being able to properly get to it, every last little bit of it, in a safe and effective way, once it was out there.

And I just said this on the previous page, and I'm going to say it again right here because it bears repeating..

In the beginning...

...they thought they could just roll the damn thing out there to the pad, completely exposed to the constantly corrosive and occasionally violent Florida beachside weather, and leave it there, uncovered, unprotected, for days, weeks, and sometimes even months.

They further thought that, once all the "hard work" of putting it all together had been done over in the OPF (Orbiter Processing Facility) and the VAB, and the fully-assembled Space Shuttle Stack, Tank, Solids, Orbiter and all, having previously been fully checked-out and inspected, got rolled out and was now sitting there on the Pad, they wouldn't need to have rock-solid tools-and-hardware access to every square inch of its very expansive and very convolute exterior surface area.

"We already put it all together with the ample supply of tools and hardware we have in the OPF and the VAB. It's complete. It's done. It's been fully checked out and inspected. Why the hell would we ever need to be able to gain that kind of access to every last little bit of it, after that? This costs too much money and takes too much time. We don't need to do this out at the Pad. We're not going to do this out at the Pad. Design your Pad Structures accordingly, shut the fuck up, and leave us the fuck alone."

"Yessir, Mister NASA Bossman, right away sir."

And so it was done.

Cryo.

Shorthand for "cryogenic." Which basically means "cold, vastly beyond the power of your human imagination to so much as even envision."

And sometimes it has the ability to make you cry-o.

And the External Tank, all 154 feet of it, which is the thing which holds the whole Stack together and also holds all of of the ultra-cold liquid fuel and oxidizer for the Space Shuttle Main Engines, the thing that holds almost every last bit of the Space Shuttle's cryo (all except for a wee little bit carried inside the body of the Orbiter which is reactant for the electrical-power-producing on-board Fuel Cells) gets filled up.

With cryo.

And so, one fine day, beneath a Florida Sky, out on Pad A, for the very first time ever in an operational wet-dress-rehearsal mode, the very first flight hardware External Tank, which had the Orbiter Columbia hanging off its side, got filled up.

At which point things happened.

And because I was over on B Pad, busily engaged in trying to convert myself from being an answering machine into being something perhaps a little more useful than that, I wasn't directly involved with the Affairs of the Day, over on Pad A, and for that reason I'm probably not the best source of information on what happened over there, but I'm all you're going to get unless somebody with better qualifications steps in, so maybe kind of keep that in mind as we work our way through the events, ok?

Gurgle gurgle, hiss hiss, glug glug goes 390,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen at 423 degrees below zero Fahrenheit into the lower portion of the External Tank.

Gurgle gurgle, hiss hiss, glug glug goes 145,000 gallons of liquid oxygen at 297 degrees below zero Fahrenheit into the upper portion of the External Tank.

A little over half a million gallons of the stuff, total, into a giant hollow aluminum bullet having tank wall thicknesses of only a quarter of an inch.

This thin skin of aluminum, by the way, is nothing less than a stupendous engineering and fabrication tour de force, and the fact that they managed to pare things down, to the point where such an enormous and heavy object as the External Tank, which routinely saw and dealt with insane thermal and mechanical forces as an ineluctable part of its given job, is testimony to the skill, cunning, dedication, and flat-out overpowering mastery of their disciplines, which the engineers who designed it, and the technicians who built it, brought to bear on their respective tasks.

But, tour de force or not, the Tank walls were still only a quarter inch thick, and that goddamned cryo over there on the other side of them is cold.

So. Spanning the full length of the LH2 Tank part of the ET, you're looking at a third of a million gallons of mind-bogglingly-cold minus 423 °F fuel, flush up against a ridiculously-thin sheet of aluminum that's not quite exactly even a full quarter inch thick.

And likewise, spanning the full length of the LOX Tank part of the ET, you're looking at roughly a mere eighth of a million gallons of oxidizer that's only minus 297 °F (Only minus 297 °F, well... that can't be too bad, can it?), flush up against that ridiculously-thin piece of aluminum, not even quite a full quarter inch thick.

And in both instances, on the other side of that ridiculously-thin piece of aluminum that's not quite a full quarter inch thick...

...you get Florida.

And you can rely on the fact that Florida is going to have something to say in the matter.

And as it does, so very many times, so very many ways, in so very many places, one of the things that Florida has to say is...

...water.

Florida comprises about one-third sand to two-thirds water. Move a little too far to one side or the other, and it becomes no-thirds sand and three-thirds water. Move up above it, and you're still getting water, and lots of it, and if you don't believe me, well then just you step outside fully-clothed, shoes, socks, and all, shirt all nice and tucked-in to make you look respectable...

...on a fine sunny afternoon in August.

Or even December, often as not.

And you will, then and there, come to understand how even the goddamned air in Florida seems to be made mostly out of water.

And that water, in the form of a humidity that has to be experienced to be believed, will take you OUT.

It has the power to flatten you, should you foolishly choose to go up against it.

And when that air finds itself in direct contact with a ridiculously-thin piece of aluminum that's not quite a full quarter inch thick, which, on its other side, is holding back roughly an Olympic swimming pool's worth of stuff that's stunningly cold, far beyond your ability to even imagine...

The water in the air will start condensing on the ever-so-cold surface of that cryogenically-backed aluminum in grand fashion.

And since there's an endless supply of that air in Florida, the process kicks into gear, and then it just keeps on going, more or less without end, and the result is...

...pretty impressive.

Even in the middle of a brutally-hot midsummer afternoon, being directly blasted by a sun which has become very angry at the world beneath it for some unknown reason, you will find yourself in possession of a pretty impressive ice buildup on every square inch of aluminum Tank skin that has cryo over there on the other side of it.

Which is not good.

Twice, in fact.

In the first place, that ice becomes quite heavy, and when we're flying our Space Shuttle, we do not want to be going uphill carrying a lot of dead weight in the form of ice, because every pound of ice that we take with us all the way uphill translates directly into a pound of payload that we will NOT be able to take uphill, and since the whole point of the operation consists in taking payload uphill, well then... that ice is very definitely not our friend.

But it's the second case that can make the hair on the back of your neck stand up, and that second case consists in the ice buildup which the acceleration and violent mechanical and acoustic vibration encountered during launch causes to break free, and fall off of the ET on our way up, with potential mission-ending consequences which result in loss of vehicle and loss of crew.

This is some seriously bad news, and it must be dealt with.

So it's falling ice that really drives the engineering from here on out.

It cannot, under any circumstances be permitted to form in the first place, lest it fall, strike a vulnerable location on the Orbiter, and damage it in a way that can cause it to burn up during re-entry.

So the Tank needed to be protected.

It needed protection for other reasons (some of which are quite interesting in and of themselves), too, but in the interests of keeping the main guts of this narrative reasonably simple and straightforward, we're going to stick with just the ice angle, and let the rest of it go, ok?

And the protection that they wound up deciding on consisted in the application of foam insulation all over the entirety of the External Tank's surface. Some of the "other reasons" for protection dictated the inclusion of thin sheets of cork, too, but for now, let's let that go, ok? Also, when you yourself decide to dig further into this surprisingly-complex area, keep in mind, that as with pretty much everything else having to do with the Space Shuttle and the Launch Pad it took off from, things changed over time, and when you find this or that document, telling you this or that thing, you have to keep it all in strict chronological order (and a lot of what you'll find will not be properly dated, and will want to mislead you as a result), because... it was a complicated sonofabitch... and it wasn't exactly the same thing... at every step along the way... every single time.

The two (harsh) chemical components which reacted with each other on contact, creating the foam insulation, were sprayed on, in liquid form, to the outsides of the fully-assembled Tanks in the Michoud, Louisiana, factory where Martin Marietta built them, and as soon as they came in contact, the resulting layer of plastic foam bubbled up rough, set into an inert solid, and was then trimmed down to a thickness of one inch in almost all locations across the full surface extent of the Tank. This Spray-On Foam Insulation was known by the acronym SOFI, and it was also the Thermal Protection System (TPS) for the tank, and you can learn a little bit more about their understanding of things prior to flying for the first time ever in 1981, under the heading Thermal Protection System, on the second page of this document.

Here, you will find a brief look at how far their analytical understanding had come, by 1985.

And here, you will find a somewhat more detailed look at how far their understanding had come, by 2004.

The engineering which surrounds the concept of using SOFI to keep the Tank in a thermally agreeable condition prior to, and during, launch might not seem too difficult on first glance.

"It's foam insulation. It's just foam. The same stuff that lines my beer cooler and keeps my brewskis cold when I'm fishing. How hard can it be?"

It is in fact a terrifyingly complicated and intractable set of interlocking engineering problems to have to solve, accurately, with the everpresent death threat of loss of vehicle and loss of crew hanging over your head as you work this stuff, and the work becomes extraordinarily stressful and high-stakes, and here's just the tip of one of the hidden icebergs which are deeply buried within, some of which remained unfound until it was too late, and they did experience loss of vehicle and loss of crew as a direct result of not having a complete grasp of the devilishly-difficult complexities inherent within this sub-discipline.

And in the beginning. Before they had ever chanced their new and never-before-flown system. A never-before-flown system containing an Olympic swimming pool's worth of cryo inside of it. A never-before-flown system they intended to fly for the first time ever with people in it.

And they thought they understood.

But they did not.

And it is the morning of December 15, 2022, and I am writing this narrative, right now, and a sharp needle of electricity has suddenly pierced my brain, bade me stop, and I obey it.

And I interject with what sounds like a low insult, but is in fact just about the highest praise I can give.

They were all cowboys back then.

We were all cowboys back then.

Out on the farthest ragged edges of things. And even beyond that, too, at times.

We shot from the hip far too many times to count.

When lives were on the line.

Our own lives.

Other people's lives.

They, on-purpose, with deliberate and specific intent, decided to build a multi-million pound Flying Volcano, and without ever having flown it before, they further decided to put people inside of it, on the very first go, and they expected it to NOT incinerate the people inside of it, and not incinerate the people outside of it, and not incinerate the whole goddamned place, and then they flew it!

And it fucking WORKED!

They pulled it off!!

They got away with it. Clean.

How can a thing like this happen?

How can a thing like this possibly come to be?

We were, every last one of us, stark raving mad.

But we didn't know it at the time.

We thought we were ok.

We thought we were sane.

And you stop and think about the balls it must have taken to willingly sign on for such a thing...

None of this could possibly have ever happened.

None of this could possibly have ever been real.

And the needle of electricity just as suddenly leaves me, and bids me return to my narrative.

I cannot know.

I can never know.

Ever.

Out on the pad, the very first tanking operation was divided into two separate work efforts, on two separate days, unlike the way it would be done prior to launch, with both LOX and LH2 being pumped into the tank more or less simultaneously.

And the first operation, conducted Thursday, January 22, 1981, where LH2 was being handled, went well, no problems.

But the second one, conducted over the following weekend, where they filled up the top portion of the ET with LOX, did not go well, and presumed thermal shock induced by the cryo that filled up the tank caused the fucking insulation to pop loose from the tank, and despite the ever-so-bland tone of our .pdf document telling us about this event, all hell promptly broke loose.

They had a launch coming up.

THE FIRST ONE EVER.

The pride of a nation was on the line.

The eyes of a nation were upon them.

They were on a schedule.

With a Program that had already endured vastly too much in the way of insufferable delays.

And they were on the home stretch.

And they could not only see the finish line out there just ahead of them, they could feel it.

And now, all of a sudden, godDAMN it, a fucking show STOPPER, and this is intolerable, and somebody had better do something, and do it NOW.

Big Excitement.

Big Deal.

Big Pressure.

And sane disinterest (as opposed to uninterest) calmly tells us, "Roll it back. Roll it back to the VAB. Roll it back to the place where there is full, complete, safe, and solid access to every single square inch of it, top to bottom. Inspect it there. Inspect it completely. Learn what you are dealing with, completely, so as you can put it to rights. Completely. You are dealing with an incompletely-tested system, and your incompletely-tested system is larger and more complex than anything of a similar nature that has ever come before. Your system has too much riding on it to be playing fast and loose with it."

"Roll it back."

But that's not what happened.

And right here is where Kafka enters the picture. Bulgakov too, perhaps.

From farthest up, on high, up in the thin air of political power where there's never quite enough oxygen to support consistent lucid thought, the dictum was handed down: "There's no way in hell you're going to roll that sonofabitch back to the VAB. That would make us look bad. And we're not going to be made to look bad. So forget rolling back, and come up with something to give that Tank a good close inspection, and then fix it, while it's still out on the pad, and make it snappy."

If only I could tell you what person, or persons, handed down this edict, I would surely do so.

I would love nothing better than to expose them to the harsh light of day, and hold them accountable for their breathtakingly dangerous and selfish actions, putting lives on the line for the worst reasons imaginable, and caring not the slightest about those lives while doing so.

All such creatures should be outed.

But this is not the way of such creatures. They do not place themselves at risk for being outed and they are very good at what they do.

They are extraordinarily skilled at remaining unseen, behind closed doors, lurking, a pair of faintly-glittering eyes set against an otherwise impenetrable background of cold-blooded darkness, a thing under a rock, a thing you will never see directly, with your own eyes.

Lovely.

Just fucking lovely.

And as in a story by Kafka, we unexpectedly find ourselves swinging wildly between opposing worlds, one that makes sense, and one that does not, and the one that does not has been placed in charge of the one that does, and...

The consequences of this disjoint are very real, which of course only strengthens the depth and seriousness of what has suddenly, without the least bit of advance warning, become very-much a life-and-death absurdity, and our protagonists, the engineers and technicians, find themselves being torn in half. Being torn asunder. Being made to serve Dark Forces which they have dedicated their entire lives to expunging from the world around them with the pure brilliant light of thoroughgoing reason and rationality.

And the Ops People on Pad A flipped out and took off as if fired from a cannon, in multiple directions simultaneously, and an entire panic-stricken cascade of events was precipitated and undertaken at a dead run.

What we're dealing with right now is only one very small part of the cascade, and only involves the wantonly-dangerous inappropriate use of existing Pad infrastructure.

But there is more. Much more, involved with that whole cascade, and we shall be immersing ourselves in it soon enough...

...but not right now, ok?

And now, go back.

Go back to the first photograph at the top of this page.

The Hammerhead Crane, access catwalk across its boom-end included, extending to the east as it is in our photograph of it, cantilevers 75 feet outwards beyond the margin of the 250 foot tall FSS which it sits on top of, 300 feet above the firebricks which line the bottom of the Flame Trench.

Now imagine yourself over on Pad A.

Same exact setup, except that now we get to imagine that there's a Space Shuttle on the Pad, bolted down to the MLP, sitting above those bricks that line the bottom of the Flame Trench.

So we're not going to travel 300 feet before we encounter something if we fall.

To the flat steel deckplates of the MLP, from up here, it's only 200 feet.

How nice.

And of course if we're suspended directly above the Space Shuttle, depending upon precisely what part of it we're suspended above, it might only be a mere 20 feet, but that's only if we're centered exactly above the tippy top of the External Tank, and even then, we either get impaled by this thing (which you're getting a close look at from a vantage-point which is roughly 280 feet above the ground, when the Shuttle is still inside the VAB, where there's full and complete tools-and-hardware access to everything, rock-solid, all the way around, all the way up to the tippiest top of the External Tank), or maybe we only get gouged by it as we glance off to the side, and continue on down the rest of the 200 feet to the MLP Deck, and whether 20 or 200, taking a fall from up here is very definitely not going to end well.

So now that we've got ourselves a clear-enough picture of what we're dealing with here, whatta ya say we short-notice jury-rig something on to our contraption, dangling down underneath the Hammerhead Crane Boom, with a float hanging from it, and go for a ride on it.

Which is the utterly-inescapable conclusion we must draw, using the one and only document still available which specifically addresses this series of events.

They very likely would have wanted to descend on their floats from something a little more substantial, something a little more easily-gotten-to, something a little more user-friendly, perhaps even something like the RCS Room, maybe, except that they did NOT know the full extent of the damage, and they were going to need to get to places on the External Tank to scrutinize it in areas where the RCS Room is not only of no use whatsoever, it's actually in the way, and yes, that means exactly what you think it means, and the whole goddamned RSS needed to be rotated back away from the Stack, to get it the hell out of the way, and once a thing like that has been done, you use what's on the Hammerhead Crane, or you don't use anything at all, so... here we go!

The relevant paragraphs of our document, "Chronology of KSC and KSC-Related Events for 1981," which was produced by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, John F. Kennedy Space Center, were dated "January 28" (a fell and fated date), and we know from reading farther up in our document that the LOX tanking test occurred some time during the previous weekend, and in 1981, the 28th fell on a Wednesday, so substantially less than a full week had passed before they determined that they were going to go after this issue, dangling below the Hammerhead Crane on a set of "floats" (note that plural usage there, and further note the lack of usage of words like "scaffold" "platform" "SPIDER BASKET" or the like), and there is no way in hell that there would have been enough time, to fabricate and install anything specific-designed of a lasting nature to get their plywood floats to where they were going, "the hard-to-get-to area, near where the Orbiter's nose is attached to the external tank," and perforce, they just winged it ironworker-style, on whatever they could throw together fast enough to get people out there to A.) Look it over closely and evaluate it accurately, and B.) FIX the goddamned thing. NOW!

Fucking cowboys!

Fucking radical!

Not that anybody ever wanted to in the first place, though.

Far from it, in fact.

But they were forced into it.

By a pair of faintly-glittering eyes set against an otherwise impenetrable background of cold-blooded darkness.

The owner of which faintly-glittering eyes, being someone we shall never know.

But these were different days, and these were different people, and once the thing had been well-and-truly thrust upon them, unasked-for, they went right at it!

Now stop.

Now walk your mind up on the Pad Deck. Up on the Tower. Somewhere nearby.

Now look.

Was the wind blowing?

We do not know.

Was it raining?

We do not know.

Was it cold?

We do not know.

We do not know, exactly, which day. Which hour.

What we do know is that we're now up on the goddamned Hammerhead Crane, with a Space Shuttle on the Pad, and we find ourselves rigging.

And we're the Pad High Crew, and this falls to us to do, and we're as good as it gets and more than just a few of us are ex-ironworkers, and even though nobody properly appreciates what we do, or the fact that without us the birds will not fly, or even knows that we exist in the first place, we're going to do it.

But as to the precise details of exactly how it got done?...

I wasn't there.

I wasn't part of it.

I'll never know.

And now we're all set up, and somebody is going to have to ride the float.

How do we get on the float in the first place?

Are we starting from up high? Scrambling across and through the handrails that line the sides of the Catwalk that runs along the full length, and across the tip end, of the Hammerhead Crane Boom? Gingerly down on to the float, unclipping the harness and then getting winched farther down from there? Sitting tight, with our tools beside us while we entrust our life to our other crewmates? People watching. Closely. From a multiplicity of locations, perspectives, and viewpoints. People running the winch to lower us while listening for shouted instructions or warnings from nearby observers and the crackle of walkie-talkie traffic coming from farther away?

Or are we starting from down low, down on the deckplates of the MLP, followed by a lengthy vertical climb, sitting, with tools, on the float the whole way?

And when we get where we're going, the black-tiled bottom expanse of the Orbiter is right there, looming, crowding in on us. We could touch the goddamned thing if we wanted to.

But we do not want to.

It's covered in eggshells, and if you break the eggshells, it will not survive re-entry, and will be lost. Along with its crew.

And the fucking wind.

It didn't feel like much at first, but now you're swaying.

You and your tools, sitting there on your float.

You're all swaying. And you have nothing to touch, to push against, to use as purchase of any kind. To control the swaying. To stop the swaying. You are at the full and unfeeling mercy of the elements. Sitting on your float, high in the air, far above the distant steel deckplates of the MLP, with an untouchable goddamned Space Shuttle, sitting there, right next to you.

And there's crew on tag lines.

And they're doing their goddamnedest best on those tag lines.

But if you've ever held a tag line in your work-gloved hands...

Paying it out, or pulling it in...

Dancing with a suspended load...

Which is not sitting still, but instead is going somewhere...

If you've ever been one hundred, two hundred, feet below something...

Or maybe only 75 feet across from something...

With a breeze...

And a mass...

And even the mere weight of the tag line prevents it from ever being drawn properly taut with a load in full and free suspension...

And it bows...

And when you haul on it...

Working against the breeze...

It will at first simply give away some of that bow, and whatever's left after the bow has been temporarily given back...

Is what actually pulls...

And there can be a sort of mushy springiness about it...

To a greater or lesser degree...

Depending...

And this is what actually counteracts twist and sway...

Is what keeps things where they need to be...

Is what keeps that goddamned mass up there in the sky above you...

Or across from you...

Or even below you...

From BASHING into whatever it is you want your suspended load to get close too...

But not touch...

And your mass is a living person on a float...

And you can NOT touch the eggshells with the unyielding hard edge of that motherfucking float...

And now the breeze is swirling around the goddamned Stack in the dark crevice between Orbiter and Tank...

And around the goddamned FSS, too...

And oh shit! I need to be over there...

Pulling like hell...

And any thing that invokes the use of tag lines attached to solid masses carrying live humans in a place like this is going, no matter how you design it, to always cause you trouble...

And...

Our band of cowboys and cowgirls...

Has somehow managed to pull this one off...

But it was a near thing...

A few of the calls were far too goddamned close...

And somewhere...

Faintly-glittering eyes are ordering a fucking martini...

Unaware...

Uncaring...

For floats, or breezes, or tag lines, or contraptions, or crews, or crevices, or eggshells, or anything in this world or the next...

Aside from themselves...

So.

Presuming this is what they did, and how they did it.

Which we do not know for an incontrovertible fact. At least at the time of this writing, anyway.

Which we have no absolute proof of that no one can gainsay.

But for which we also have nothing whatsoever to the contrary by way of alternative explanation for how they got it done...

They got it done...

...hastily...

...sloppily...

...dangerously...

...and yet at one and the same time with virtuoso competence and mastery...

...with regards to both equipment and personnel...

...using something...

...trustworthy?

...reliable?

...sane?

...safe?

...nah...

...they were handcuffed...

...and they were forbidden from doing the right thing...

...and what they wound up having to use looked like this, and yes, this is a fine general-arrangement drawing, but no, it does not make enough sense in and of itself, so whattayasay we dig a little deeper, farther down into it?

But before we do that, take note of the title of our 79K24048 general-arrangement drawing for this thing, S-219, "FSS-El 300' Hammerhead Crane Trolley."

It almost makes sense.

It almost tells us what's going on here.

Almost.

But not quite.

That title gives a very strong impression (and yes, this sort of thing is very real in this industry) of having been ever-so-carefully crafted to cause you to think it's telling you something useful, when in fact it's doing no such thing, and in further fact is actually obscuring that which it really is.

"Trolley" is it?

Very well then, it's a "trolley."

Trolley... what?

Trolley... for what?

Dead silence. Yet another lie of silence.

The worst sort of lie that can possibly be told, because it's damn near impossible to find it and recognize it for what it really is.

A button-down shirt somewhere (On their own? At the behest of someone above? We shall never know.) passes casually by a drafting desk, notes what's there in the title block, and even more casually informs the draftsperson that's producing the drawing that "We'll need a better title for this one," supplies that title on the spot, and then just as casually continues on, back to their own office without so much as another word.

And yes, this kind of thing is real, and yes it really does happen, and I'm sure you have seen (or, if you're young, will see) more than enough, similar, in your own life, but sometimes they slip up.

Sometimes things slip through.

And in this case, the drawing itself joins in the silence...

...but not quite...

...and it has to direct us elsewhere for some electrical work...

...and when we go take a look, over in the 79K24048 electrical package, over on drawing E-502, where our button-down shirt seems not to have gone...

The full truth of the matter becomes plainly visible.

And yeah, this is all starting to sound unpleasantly like a bunch of crack-brain conspiracy-guy shit, but...

This whole thing was a major embarrassment to certain... entities.

And this whole thing was enough of an embarrassment to cause them to literally prohibit the Operations People from doing the right thing. From rolling back to the VAB to properly rectify this nightmare.

And concomitant to that prohibition, whoever it was that handed it down from on high was perfectly happy to take the risks (which risks, of course, had they materialized into an incident would have been pinned on someone else) which included the potential for severe, and even catastrophic, damage to a national asset, and potential loss of human life.

These fucks were playing for keeps, and once you reach a level of corruption that's willing to go to lengths such as this, you may very reasonably expect that as a part of their machinations, they very much would have wanted any further efforts along similar lines, and any further signs of those efforts, to be kept low. Kept quiet.

Prove me wrong.

Prove me unreasonable.

I stand ready to accept such proof and rewrite every bit of this.

But you'd best be bringing your very best proof.

You're going to be needing it.

Because this whole thing was rotten to the core.

And we're not done with it, just yet, either. There will be more.

Ok.

Enough drama.

Enough politics.

What are we dealing with here, technically?

They were up there underneath the Hammerhead Crane, dangling down in a Spider Basket, inspecting the Thermal Protection System on the External Tank, and they needed some reach to get to all of the places they thought they might need to get to, and so they designed accordingly.

All well and good.

How much reach do they get with the Crane, all by itself?

Let's look at a drawing that gives us a close view of the Crane, so as we can start to get a feel for what's going on here with this stuff.

79K10338 A-20 shows us the crane in pretty good detail, and it also contains some good hard dimensions, and even though they are lift radii, they turn out to be quite useful, because they let us move, using the same scale of lift radii, a cut-out copy of the Crane into to a different drawing 79K14110 sheet V-9, which shows us the whole area of the Pad Deck, including the same lift radii, and from there, we can do a little work, and maybe get a good-enough feel for exactly where we are, what we can reach, and what we can not reach, before we pitch back into the details of the kludge which will (supposedly) allow us to, from henceforth, access areas on the Stack that were heretofore inaccessible, out on the Pad.

So.

And here's 79K14110 V-9 again, showing us the Pad Deck, with the Hammerhead Crane carefully grafted on, exactly to scale, so as we can get a look at things in relationship to each other.

And we stopped here along the way because things get cluttered, and when I graft the Stack, mated to the RSS, onto V-9, without having first seen the Crane by itself, it's not quite as easy to visualize, so I went ahead and cut you a little slack by stopping with just the Crane pasted in there all by itself, before moving on, ok? Doing it this way lets us still see the whole place, FSS, Pad Deck, Flame Trench and Deflectors, RSS Curved Rail Beam, and all like that there, so as we're able to have that clean view in mind when I finish up by pasting a bunch more crap onto the drawing, making the overall sense of things less clear, less visible, and less easy to deal with.

But what we're interested in has yet to show up, so let's drop that whole mess into V-9, and now we can see, clearly, that which we were originally looking for, which is the amount of reach we get if we find ourselves having to use the goddamned Hammerhead Crane all by itself to gain access to the External Tank, which is a thing that The Little Baby Jeesus Up In The Sky never intended be done, and which will make him cry when go ahead and do it anyway.

Observe.

In all of its gobbed-up glory.

79K14110 V-9 with a Hammerhead Crane, plus the complete Space Shuttle Stack, further complete with the RSS that it's mated to, telling us loud and clear that yes, by coming down from off of the Boom End Catwalk, we can just barely reach the bipod area on the Tank where the forward attachment point for the Orbiter is located where the SOFI popped off when we filled the LOX Tank portion of the ET out on the Pad for the first time ever, but god help us if we wish to go so much as one more inch farther away, 'cause that Crane Boom ain't gonna cut it if we want to do a thing like that, and if we ever decide we might want to do a thing like that (and of course they did), then we're gonna have to come up with something, and that "something" is what you're seeing in the first photograph up at the top of this page. And oh yeah, now you can see how the RCS Room is completely useless for the purpose of hanging floats down from it to get to... pretty much anything having to do with the Tank, so that's right out as a possible solution, and... we're in a pretty tight jam here, all the way around.

Got it?

I sure hope so.

So back we go, once again, to our Extensible Pipe Boom Nightmare, and now, finally, we can all understand, plain as day, what this thing is really going to be doing for us, and why it had to be designed and built the way it was, to do that, and the first thing that oughtta be jumping out at you from off of that drawing like a rattlesnake striking from its hidden place in the thick grass is the fact that our Extensible Nightmare is going to be giving us almost 30 feet of additional reach beyond the far end of the Catwalk which was the end of the line, previously.

And what, pray tell, might we be able to do with a thing like that, hmm?

Whattayasay we go and put even more crap on poor old drawing V-9, and see if it tells us anything?

And MacLaren, being MacLaren, adds up the dimensions given on S-219 for the boom in its extended position, ignores the small deduct for the end-stop, and gets a radius, from the centerpoint of the Hammerhead Crane's rotation, of 128'-5¾", tells the ¾" to go away and absorb itself into another full inch, which then takes him to 128.5 feet, which is much easier to work with on his graphics program (I'm a Linux guy, and I use GIMP), and he then scales to the existing drawing, and he lays it down with a nice solid dark-green line.

Behold.

The glories of additional reach.

And by golly we see that this thing they made us fabricate and install, will now give some unfortunate, riding in a Spider Basket (if they're lucky) hanging from beneath it, full and complete access to not only the whole External Tank, but also both of the SRB's, and even most of the Orbiter, excepting what appears to be maybe a little less than the last ten feet of the Right Wing.

Yes, yes, I know, I know, you're never supposed to do any real engineering this way, and if you try, you will kill people and wind up in jail, and the lift-radii circles are not even exactly perfectly round, and the whole goddamned drawing is bent (you cannot imagine what I have to go through with each and every one of these goddamned things, taking the sickeningly and uniquely distorted individual originals, trying to bring them back in, trying to get them straight enough, and no, they're never going to be perfectly "straight"), but for giving us the requisite sense of things, this work is plenty accurate enough, so it's ok, and by damn we're gonna use it.

So ok. So now we know all about it. Where it will take us. Where it will not take us. And what's there, in the places where it will take us, and also, in the places where it will not take us, so now that we've finally gotten all of that squared away, let's go build it, and after we've built it, well then let's go hang it on the tower.

Gotta build it before we can hang it, so let's go look at a few drawings and see how that works, first.

And it's just about the daffiest goddamned thing you could imagine.

It's a monorail, hanging under...

...another monorail!

Yep. It's a monorail for a monorail.

I've never been able to quite figure out why monorails in this place are so... goofy, all the time.

We've already seen more of this goofiness with monorails than you could ever expect to see on one job, and...

...there's more to come with it.

Big Monorail Fun on Pad B.

But not yet.

We need to finish here, first, ok?

Now... where were we?

Oh yeah, a monorail for our monorail.

Which bolts up underneath the Hammerhead Crane Boom, and which is almost, but not quite, blocked from view in our first photograph up at the top of this page.

This thing.

Which is the thing that holds up the thing, and which, in and of itself, is no trivial item, and requires a fair bit of tricky welding in a few awkwardly-tight places, hanging on floats beneath the Hammerhead Crane Boom, putting in stiffener-plates of various shapes and thicknesses (go back and get a look at that stuff on the drawing, down below the elevation view of the monorail that I labeled and shaded in blue, go click the link to the drawing again, and just look at it) to beef up the Crane's existing W14, and to then weld support brackets onto the bottom side of its bottom flange, splice and match-drill the new monorail (which, this time, turns out to NOT be one of the common A36 S-Shapes we've been encountering all along for our monorails up to this point, but instead is an expensive purpose-designed composite shape made by American Monorail, and is a surprisingly tricky thing, in and of itself, and here's a PDF that tells you all about it), and then bolt that sonofabitch on, plumb, square, and true.

And now, with at least half an idea of what it is we're looking for, let's go find it (almost, but not totally, blocked from view) in our first photograph up at the top of this page.

And you don't get much, but you get just enough, and now you can sort of get an idea of just how much fun it must have been to get this thing crammed up under there, 300 fucking feet up in the goddamned air, after you'd had to weld up the stiffeners above the bottom flange of the W14 it's hanging underneath, and then weld the support brackets on to the bottom of that same flange, and then thread that pair of trolleys onto it, and then finish it off, bolting splice plates, bolting end-stops, and then bolting the whole schmutz to the support brackets, and every one of those bolts and the holes they went into had to be dead-nuts exactly where they had to be, and you can bet your ass that were were drift pins and beaters singing in the curse-filled air whole time, and what might the weather have been like on those days, and...

No. No fun at all. None of it.

And we've only just finished hanging the thing, that carries the thing, and that thing is next.

So here ya go, 79K24048 sheet S-220, which shows us our Extensible Pipe Boom in all its ridiculous glory.

And you need to stop, and consider this thing.

And what it did for a living.

And how it did it.

Sixty-four and a half feet of sixteen inch diameter steel pipe.

And that's just the beginning.

Then they called out yet another expensive special composite-shape monorail to weld up underneath it, full-length. Same deal as the other monorail from American Monorail that this mess is hanging from.

We've seen the .pdf for that monorail already. And it was a three-piece weldment. A36 top flange, welded on to an A36 web, with a specialty-rolled high carbon-manganese WT section welded to the bottom of the web. Very much a non-trivial piece of material.

American Monorail had their own fabrication shop, and at some point, somebody's gotta fit and weld the top flange to the web, right?

Ok.

So what's the first thing the people who had to make the Pipe Boom have to do?

That's right, the first thing they had to do, is come right at that composite-shape monorail, and decapitate it.

Cut the top flange right back off of it and throw it away.

Does this make any sense?

Nope.

But that's what they're told to do, very sneakily I might add, in Detail B on S-220, where they don't actually come right out and tell you exactly how much of the top of that thing needs to disappear.

Oh no. That would be too easy. That would be giving it away.

So instead, you get a dimension from the centerline of the pipe, to the bottom of the bottom flange on the no-longer-quite-as-composite-as-it-used-to-be monorail, and... "Hey you, yeah you, over there on the shop floor, you figure it out, ok? And don't go fucking it up, either, or it's gonna cost the company a bundle if you do."

And then of course all the trim work involved with support brackets, trolley and caster attach points, and end-pieces that goes on after that, which in and of itself, is pretty substantial.

And when it's done, you haul it from the fab shop on out to the Pad (Again, very much nontrivial. Just simply hauling the damn thing. Sixty-four and a half feet long. How's that gonna work on the local highways when it has to turn left at this next traffic light, hmm?), and after the fixed monorail that supports it is has already been bolted on to the underside of the Hammerhead Crane Boom, you winch it up there, and then it becomes the ironworker's problem, but those people are as good as it gets, and your stupid thing is very definitely not going to stop them.

And when it's all together up there, the Pipe Boom part of it rolls back and forth, outward and inward, from a stowed position tucked all the way up beneath the Hammerhead Crane Boom, to a working position where it sticks thirty some-odd feet out past the end of it, and back again, whenever they decide they're gonna need to use the goddamned thing (more, oh yes, much more to come about that whole "use" deal, so kinda be looking out for it when it gets here).

To extend and retract the Pipe Boom, they would pin it to the Crane Hook Trolley on the Hammerhead Crane, and then run the Crane Hook in and out, dragging the Pipe Boom along with it as they did so.

And naturally, when we foolishly ask ourselves if any of the procedure for doing any of this stuff is spelled out anywhere on any of these drawings... the harshly-shouted answer comes right back at us, "Of course not, stupid, these are PRC/BRPH drawings, and they're garbage!" so we just sort of figure it out by process of deductive reasoning, and think of all the money PRC saved by not spending a minute of their ever-so-precious time on such a patently unnecessary and wasteful activity.

Needless to say, for a thing like this to work, the Pipe Boom, along with its Support Brackets which were welded on to the pipe itself and stuck up from there a pretty good ways, could not be touching anything as it moved.

And we go back and look at S-219 again and... yep, there it is, they're specifying a half-inch of clearance when the thing is being trundled out, and then back in again, although it's not the kind of thing that would jump right out at you, and is plenty easy enough to miss.

All well and good, but what happens when they've got the damn thing where they want it, extended or retracted? How the hell do they keep it from getting away from them, once it's where it belongs?

And yeah, it's "right there" on the same drawing, there on S-219, and you even get it a second time, on S-223, but in neither case is it ever actually spelled out as a sensible procedure, and instead, you get to just sort of infer that's what you're supposed to do, based on the less-than-fully-wonderful notes and those weency little lines which tell us (we hope) that there's bolts that go between the top of the Pipe Boom Support Brackets, and the bottom of the uppermost Fixed Monorail Support Brackets that got welded on to the Hammerhead Crane Boom W14.

So yeah, you draw it up by torquing those bolts (and just imagine how much fun that must have been, each time they unbolted it, moved it, and then bolted it back up), and no I don't see any access platform for anybody to be standing on when they did this work, either, and I guess they just tied off and climbed on out there, reached down or skoonched down (don't slip, don't fall, it's a god-awful long drop to those bricks that line the bottom of the Flame Trench down there), or some damn thing somehow, down below the bottom of the W14, drift-pins beaters and spud-wrenches in hand, and... pshit. Buncha damn junk is what this thing is.

That W14 is also what carries the rail, that the Crane Hook Trolley rolls in and out on, too, and let's go maybe get a look at such pittance of detail they deem it fit to give us about all that, on S-223, ok?

And it's complicated (but by now we've come to expect that, right?), and they're pretty damn close-mouthed about all of it (again, it has become expected, right?), but if we look close, we can figure it out, while we admire their goof-ass system for pinning the Extensible Pipe Boom to the Crane Hook Trolley, to run the Pipe Boom inwards and outwards along the length of the Hammerhead Crane.

Phew!

So here's all that, right here, on S-223.

And we still haven't even gotten to the thing that would run the trolley which held up the Spider Basket (Remember the Spider Basket? It's the whole point of this psychosis. And on at least one occasion they used floats instead, and we don't know how they did that, but that's not the point right now.) back and forth along the entire length of the decapitated-monorail which was welded up underneath the Extensible Pipe Boom. Gah!

So...

Check this out...

The thing that runs the Trolley, that holds up the Spider Basket, back and forth along the decapitated monorail that lives up underneath the Pipe Boom.

Whoa!

And yet again, they're not telling you anything, but if you look at the dimensions which locate this thing midway along the length of the Pipe Boom, and you then go back and look at S-219, showing the general arrangement of the whole contraption in its extended position, you can see that when it's out there, this actuator (that's not really the right word, but damned if I know what to call it) lines up with the far end of the catwalk that runs crosswise at the end of the Hammerhead Crane Boom.

And from out there, one of the techs stands there and manually operates the goddamned thing, and "Say, Lou, how 'bout this weather out here today, and my brother-in-law told me it sleeted over in Osceola County yesterday morning, and he even sent me pictures of it."

Let's go back to S-222, which I've marked up to help you understand the "sense" of it, now that you know what it's there for, and how they work it.

Can you believe this thing?

And yeah, that's the hand crank for it that you saw over there to the left side, on S-223 and...

And there's a part of me that cannot shake the feeling that this whole thing was designed and built the way it was, because somebody was pissed off.

Because somebody knew the entire underlying concept for this thing was bullshit, and guessed correctly what they were gonna wind up doing with it one fine day.

"You're not gonna let us roll back? You want to put the whole fucking program at risk because you don't want to be made to look bad?"

"Really?"

"Is this really what you're telling us to do?"

"Well then, fine."

"We'll do it."

And oh boy, did they ever do it!

Again, no proof whatsoever that any such thing was even imagined, nevermind actually implemented...

...but I've seen it happen.

It does occasionally happen, and the more somebody feels like they're being cornered, into a particularly unpleasant corner that will lastingly have their name attached to it...

And sometimes it sails right on through the entire review process, from drafting table to NASA upper management and right back down again, and nobody picks it up...

...and it gets implemented.

So who knows?

Not me, that's for sure.

So.

That's the story of the Extensible Pipe Boom, right?

Now that we know allllll about it, we're done, right?

Nope.

We're not done.

Kafka has not left the building.

And neither has Bulgakov.

We're not done.

In fact, we're just getting started.

On the part that has the power, all these many decades later, to cause my blood-pressure to rise to dangerous levels.

I was now working for Ivey Steel.

And I was no longer any kind of answering machine and in fact, by this time, answering machines, and pagers, and a few more rudimentary precursors of what was to come, had been invented, and were in wide use, and nobody ever needed to hire a warm body to sit in a chair all day long, waiting for a black rotary-dial telephone hardwired to the wall, to ring, so they could pick it up when nobody else was around.

Those days are gone, and they're not coming back.

So what was I?

I was the assistant to the Project Manager (Dick Walls, yet again), which made me a construction manager. Low-level, to be sure, but very much NOT an answering machine.

Ok, fine, get to the fucking POINT MacLaren.

And this ridiculous Extensible Pipe Boom had already been furnished and installed over on Pad A, and when you drove past that Pad, you could see it there, plain as day.

But following the initial events, it seemed as if the allergic reaction to rolling back had subsided, and in the history of the Program, there were several rollbacks, to address different problems at different times.

So by this time, the stupid thing hanging beneath the Boom of the Hammerhead Crane over there on Pad A seems to have become unnecessary. Obsolete. Not required.

Enter Ivey Steel, along with MacLaren, who's now generating paper.

And it came time for this Grand Stupidity to be installed beneath the Hammerhead Crane on Pad B.

Shortly before which time, you could look across to Pad A in the distance, and see that they were in the process of REMOVING IT FROM THE HAMMERHEAD CRANE.

And down to the ground it went, whereupon it was cut into pieces, and hauled off to the KSC Landfill/Scrapyard at Ransom Road.

And with our own eyes did we see this.

And we had yet to furnish and install this monstrosity, so we stopped and asked ourselves, "Do they really want us to do this over here? They just tore it off Pad A, and we know for an incontrovertible fact that it's going to get the same treatment over here on Pad B... so why put it up there in the first place?"

And we worked up a CREDIT to the contract, fair dollar value for labor hours, material, and overhead costs, not expended, which would be returned to NASA, in exchange for not having to fuck with it.

We wanted to do the right thing.

And it was yours truly, James MacLaren, who wrote that paper.

Somewhere, buried deeply in their system, that piece of paper, or a microfiche, or an electronic image of it, still remains. With my signature on it.

Best of luck finding it.

And my piece of paper went out the door, and went to the Prime Contractor (Sauer Mechanical), and from there it went to NASA.

And after NASA deliberated over it for a week or two, it came back.

DENIED.

No credit will be accepted!

Furnish and install it as per the terms and conditions of your present contract.

And we were flabbergasted!

We could not believe it.

And there was a LOT of informal back-and-forth between ourselves and their people who worked in differing areas, engineering, operations, scheduling, cost accounting, you name it, and NObody was ever able to STOP the goddamned thing, and in the end, WE BUILT IT, AND WE HUNG IT ON THE TOWER.

Just like you're seeing us do in those three photographs up at the top of this page.

And then, after the thing had been left sitting there for a pretty good while in its very out-of-the-way location, ignored, unused, while we continued working elsewhere on the towers, we were given an amendment to our contract.

A change order.

Which extended our contract, and paid us fair value for the extra work it included.

Take the entirety of the TPS Inspection Spider Basket Trolley Extensible Pipe Boom Assembly down.

Cut it into pieces.

Haul the cut-up pieces to Ransom Road and turn it over to the NASA operatives who run the place.

And we did it, down to the last detail of getting a receipt for it at the scrapyard!

Exactly as we were instructed to do it.

At which point it was gone, after never having been used even once, as if it had never existed in the first place, and all that shall ever remain will be these photographs of it, up at the top of this page.

All of it, every last bit of it...

...for nothing.

At which point Kafka and Bulgakov give each other a hearty high-five and leave the room.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEContact Email Link |